Dalkey Archive Press Ireland - An Interview with John O’Brien

We talk to John O'Brien of Dalkey Archive Press about their Creative Europe Literary Translation Project which will support the translation of ten works from ten countries.

Creative Europe supports the translation and promotion of European literature as a means of enhancing knowledge of the literature and literary heritage of fellow Europeans. European publishers can apply for EU funding for the translation of a package of up to 10 works of fiction from, and into, European languages. Funding is also available for the promotion of the translated books. Thirty-nine literary translation projects by publishers in sixteen countries will receive a combined total of €2.1 million.

Under this round the selected projects will account for 322 translations altogether. Each project will translate eight books on average. Not only novels stand to benefit - children’s books, short stories, poetry, and plays also receive translation support.

A list of the selected translation projects and more information on the applications by country is available on the Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency website.

DALKEY ARCHIVE PRESS IRELAND AND THEIR CREATIVE EUROPE PROJECT

Dalkey Archive Press Ireland were selected for their project Internationalising Eastern European Literatures. Dalkey Archive Press received €60,000 under this funding strand to support the translation of ten works from the following ten countries: Serbia; Montenegro; Poland; Bulgaria; Slovakia; Croatia; Slovenia; Turkey; Bosnia and Herzegovina; and Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia.

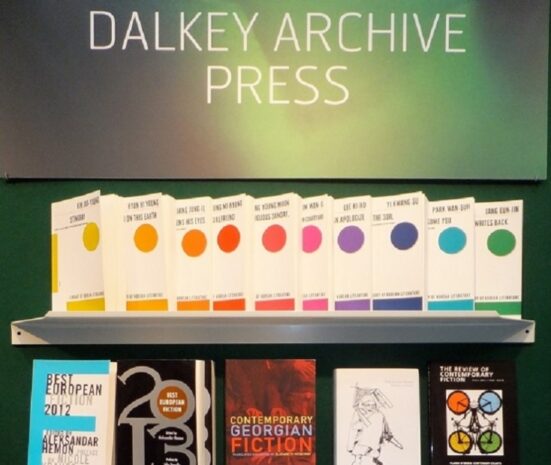

The Dalkey Archive Press (named after Flann O’Brien’s novel, The Dalkey Archive) specialises in the publication and re-publication of high quality and out-of-print works, particularly modernist and postmodernist. A non-profit publisher, founded in 1984 by John O’Brien in Chicago, Dalkey Archive Press has well over 400 translations in print from 47 different countries. With offices in Illinois, Texas, and in Trinity College, Ireland, the publisher aims to create an international forum for the publication and discussion of literature from around the world.

INTERVIEW WITH JOHN O'BRIEN OF DALKEY ARCHIVE PRESS

1. Congratulations on receiving this award! Can you tell us a little about the Internationalising Eastern European Literatures project and how this Creative Europe funding will help Dalkey Archive Press?

John: Keep in mind that virtually nothing from non-English languages is being translated into English. Of the 350 - 450 translations, about a third are from French, German, and Spanish. The rest of the world? Quite often no literary books are translated from several countries. And do not assume that all of these translations will ever be heralded as great works of literature. So, despite English now being the lingua franca, we are quite isolated from the rest of the world via language, and the highest forms of that literature. Dalkey Archive has been actively pursing literature from what is generally called 'Eastern Europe' for many years. My view is that there are more interesting and daring writers coming out of countries like Serbia, Romania, Slovenia, Croatia, the Czech Republic, and Macedonia than from France. All of these countries sponsor programs to help defray the expenses of publishing translated literature, but that rarely goes beyond 10 - 20% of those costs.

Creative Europe's program is of course welcome by Dalkey because this program allows us to receive more support towards those costs. And yet, so much more is needed. I more or less grew up on translations, but that was at a time when commercial houses were publishing an enormous number of books from around the world. But that started to end in the 1970s and early '80s, because these houses faced the fact that such books did not pay their way and add to the bottom line. This was also the time when these same houses begin to put a large number of books - some of our finest literature - out of print.

In the early '80s, therefore, I started by quixotic venture to go against the grain, to fight the trend that had started, and to try to create a space in the culture where these books could be published and kept permanently in print, and to insist that large numbers do not determine quality nor does immediate popularity. My view is that these works must stay in print, be actively promoted to future generations, and that their significance will grow with time. It grieves me to say that neither Ireland nor the United States has special programs to combat the situation we are in as regards translations. The National Endowment to the Arts in the United States has consistently demonstrated either an indifference to or a hostility towards translations, though it bristles with indignation when this is brought to their attention. A number of years ago I would be told what objections some panel members had to our applications, and in almost all cases the objections centered on panelists not seeing how translations benefited the public and further objected to American money going to writers who weren't American. If some of what I'm saying here seems to have application to American politics today, so be it.

2. What kind of works will be translated and how will Dalkey Archive Press choose the writers and translators?

John: We had to choose the writers ahead of time, and we had a rather brilliant editor at the time and her tastes perfectly aligned with the Press's. The quality that characterises all of them is an interest in what fiction can do when it is set free and does not have to produce a novel or short stories that will appeal to thousands and thousands of people. They are frequently very funny and also frequently on the dark side. They are writers with a vision and writers with a distinctive voice that must be heard beyond their own language.

3. Is it more difficult to find and read works in translation these days and how does Dalkey Archive Press help to address this difficulty?

John: I could answer this in any number of ways, and some people in the so-called translation community insist that there are more literary translations than ever, but the numbers do not support this. The numbers haven't changed in ten years. Even funding agencies have come to believe this grand illusion. I suppose this must make everyone about how grim the situation is. Dalkey tries to address this difficulty by publishing about 50 translations each year, just a few translations behind Amazon's translation line of books. So here we are, next in line to this billion-dollar company but lacking their billions.

There is a very sharp drop off after that. But this effort gets more and more difficult, and largely because of the lack of government or philanthropic support. Dalkey now has approximately 800 books in print, and just keeping those books in print costs a great deal. What I do not want to have happen is to have Dalkey end when I do. Our list is a kind of monument to some of the best literature of the last several years and it remains available regardless of sales numbers. We remain in need of a financial base that will carry the Press into the distant future, so that one day that 800 will be 1600, and our ability to reach readers will not be inhibited by the shortage of money.

4. When and why did you set up the Irish office of Dalkey Archive Press? Is the Irish office a bridge to European writers, their works, and the European literary world?

John: At the time, my hope was that the Arts Council would be a significant supporter of Dalkey and that Dalkey would find a permanent home at Trinity College. Over a period of time I wanted Ireland to be the headquarters for the Press and that the United States would be a satellite. I knew America already and could continue to run things successfully there, but I did not know Europe and how the book business functioned here. It was, and is, also the case that the Press has been deeply influenced by European literature, even on down to the name of the Press. I felt I had to be in Europe far more than I could be by short trips here. The choice was London or Dublin, and it's clear which one I chose. We of course have complete legal status here, we are expanding our readership in Europe every year, and we are able to have much more contact with our authors.

5. How did you approach your Creative Europe Literary Translation application? Have you any advice for others who wish to apply?

John: We mapped out ahead of time what we thought would be required and gathered those materials. And we read a few dozen books. But before doing anything serious, we waited for the guidelines to come out, wrote a rough draft, and then went for advice to the Creative Europe Culture Desk. The people there are brilliant, and not just in knowing the guidelines inside and out, but explaining why you should emphasize one thing over another. Publishers seem to have great difficulty with the applications and requirements, but since Dalkey Archive is a nonprofit, we have had to conform to these requirements for years. The rules and regulations are not as onerous as they might seem on first reading. Talking to the people at the Culture Desk is, I think, essential.

6. Have you some favourite works in translation, from Dalkey Archive Press, that you might recommend to readers to whet their appetite in advance of your ten new translations?!

I could wind up naming a few hundred books by way of answering your question, but I will limit myself to the ones that come to mind first, all ones that I think are extraordinary in so many ways. Here, in no particular order, they are: Vain Art of the Fugue by Dumitru Tsepeneag (Romanian); Chinese Letter by Svetislav Basara (Serbian); Learning Cyrillic by David Albahari (Serbian); Palinuro of Mexico by Fernando del Paso (Mexican); Melancholy by Jon Fosse (Norway) who won the European Prize for Literature in 2014; Some Thing Black by Jacques Roubaud (French); Night by Vedrana Ruden (Croatian). There are so many others that could be on this list!

Many thanks to John for his candid interview and for his book suggestions. We look forward to the forthcoming ten translations which will be published under the Internationalising Eastern European Literatures strand. The Creative Europe Desk Ireland - Culture Office is here to assist you with any queries you might have about any of the Creative Europe Culture funding strands. Please contact Audrey Keane or Katie Lowry at cedculture@artscouncil.ie if you have any queries about funding and applications.